From 1899 to Now: How Songwriter Contracts Have Evolved

When we talk about iconic pieces of American music, Maple Leaf Rag by Scott Joplin almost always comes up. But beyond its musical influence, the story behind its publishing deal also says a lot about how songwriter contracts used to work—and how much they’ve changed since 1899.

As a Music Business student concentrating in recorded music and publishing, I wanted to revisit Joplin’s original agreement and compare it to the kind of deal an emerging songwriter might face today. Even though more than a century has passed, the basic power dynamics between writers and publishers are surprisingly familiar.

1. The 1899 Deal: Simple, Harsh, and Very Old-School

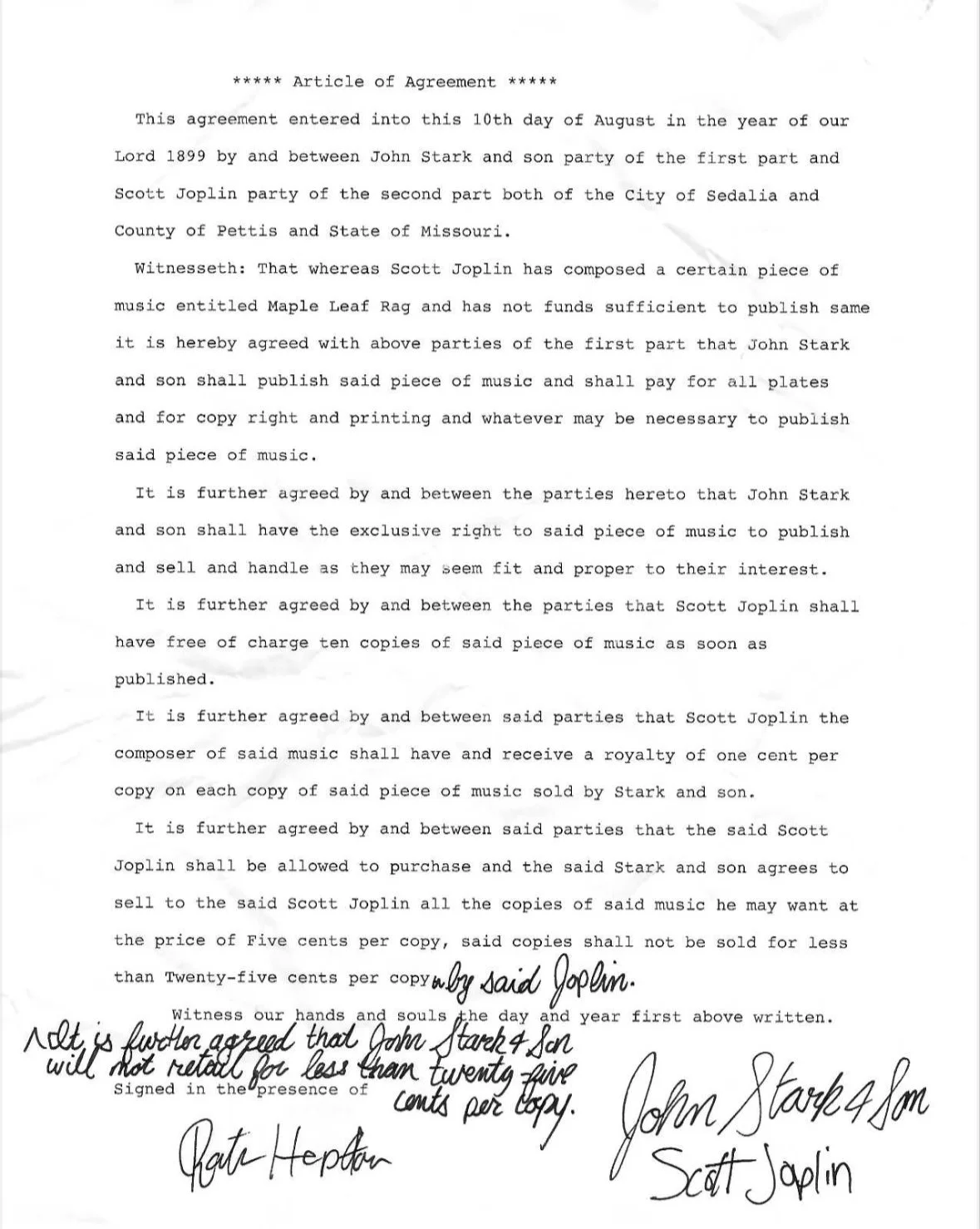

Back in 1899, Joplin had a great song but no resources to publish it himself. Publisher John Stark stepped in, bought the copyright for just $50, and took full control of Maple Leaf Rag. Stark paid for plates, printing, and distribution, and in return, he owned 100% of the copyright.

Joplin’s compensation was straightforward:

1 cent per printed copy sold

10 free copies

the option to buy additional copies wholesale for 5¢

and that’s… basically it

No advance, no reversion clause, no term limit, and no split like the 50/50 deals we see today. If anything, this contract is an early prototype of a single-song traditional publishing deal, just far less generous.

2. Breaking Down the Terms in Today’s Language

If we translate the 1899 contract into the way we talk about deals now, it would look like this:

Grant of Rights: Publisher owns everything

Exclusivity: Applies to Maple Leaf Rag only

Term: Not stated → likely perpetual

Royalties: Flat rate per printed copy

Advances / Delivery / Reversion: Not included

Territory: Not specified

It’s simple because publishing itself was simple at the time. No streaming, no sync, no PROs, no global licensing systems—just sheet music sales.

3. What Would the Modern Version of This Deal Look Like?

If a “modern Joplin” showed up today with one promising song, they’d probably be an independent songwriter with no previous cuts or hits. A modern version of Stark would likely be a small indie publisher—the kind that takes risks on early-stage talent.

The most realistic deal?

Single-Song Traditional Deal

And here’s what would change:

✔ Term

Modern deals always include a defined contract period, commonly 3–5 years.

✔ Royalties

Instead of 1 cent per printed copy, revenue today comes from:

performance royalties

mechanical royalties

sync licensing

digital sources

The publisher keeps the publisher’s share, and the songwriter keeps the writer’s share (50%).

✔ Advances

Very new writers often get no advance, or something symbolic (like $300–$1,000). Definitely nothing like a large co-publishing advance.

✔ Territory

Standard today: Worldwide or even Universe.

✔ Reversion

Some indie publishers might include a reversion clause, but usually not a generous one for beginners.

Even after all this time, one thing hasn’t changed: new writers rarely have leverage. Publishers invest time and risk, so they negotiate from a stronger position.

4. What Today’s Songwriters Can Learn from Joplin’s Deal

Even though the industry has advanced dramatically, the structure of publishing deals still reflects the same core ideas:

Leverage matters more than talent.

Joplin believed in his own success but still couldn’t negotiate better terms.Copyright knowledge is essential.

He signed away his rights permanently—today’s writers should understand what they’re giving up.Publishing is still a business of risk and reward.

Publishers take financial risk and want control in return.A single song can change everything—but only with the right deal.

Maple Leaf Rag became huge, but Joplin’s contract didn’t reflect that success.